[1]

[1]MOULTRIE, Ga. (BP) — The clock is ticking.

At the stroke of midnight on Thursday, undocumented residents who were brought to the United States as children will no longer be able to apply for deportation deferral. For the last five-and-a-half years, Georgia Baptists in Colquitt County have been working to help as many as possible — in a state that reportedly has some 24,000 who are undocumented — complete the paperwork which would temporarily delay them possibly being removed from their families and returned to their countries of birth.

Georgia Baptists are known by many for their literacy missions work and helping those legally in the U.S. complete their path to citizenship. Involvement with the DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program) ministry falls under the possibility that DACA could provide recipients a path to citizenship — and keep the family unit intact. But that citizenship is not automatic.

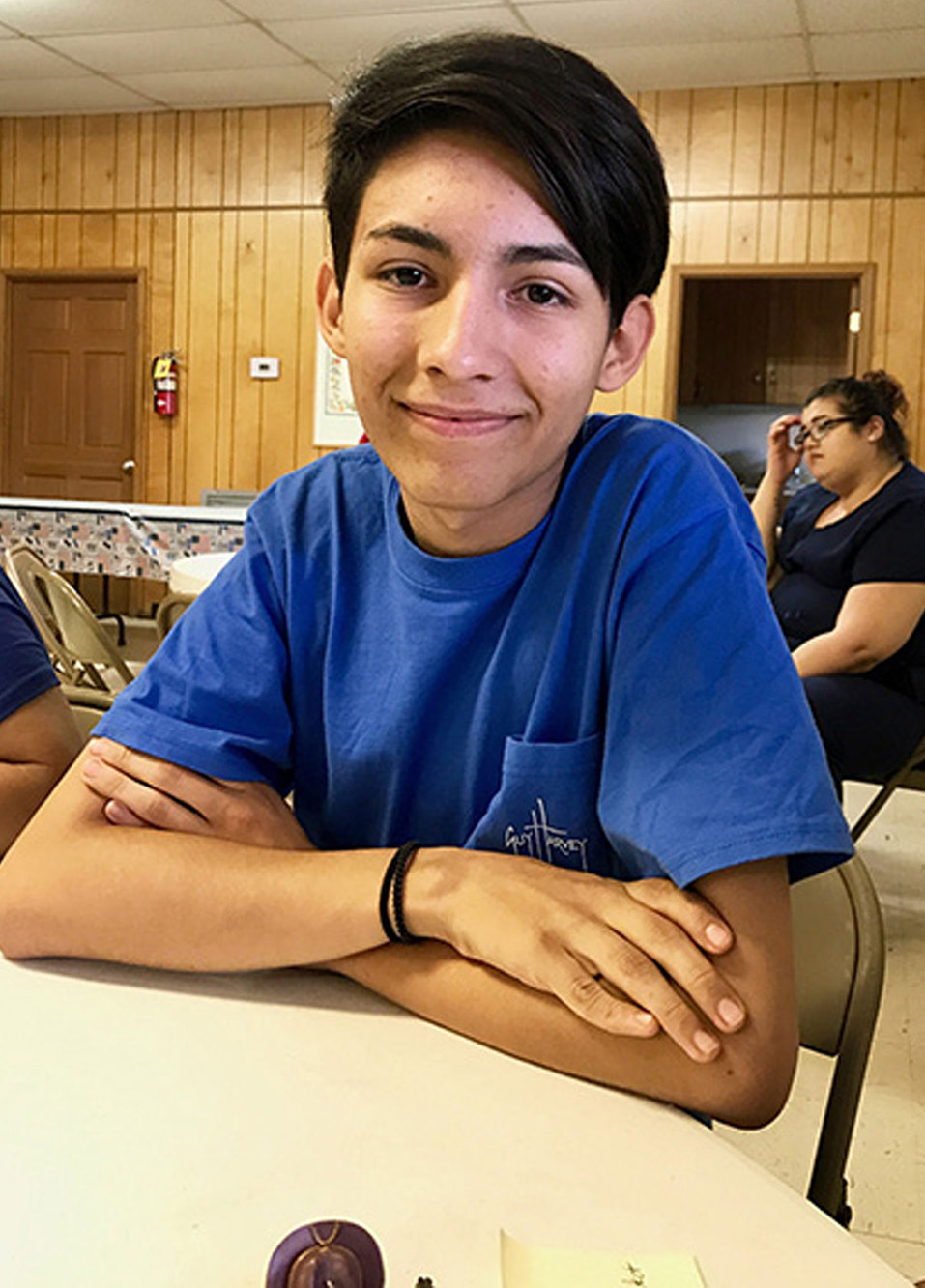

DACA qualification is rigorous and requires a nearly-perfect record, free of virtually all encounters with law enforcement. That is why, for numerous Thursday nights, Memorial Baptist Church in Moultrie, Ga., has been helping young teens like Jonathan Cervantes avoid deportation.

His first encounter with the church was through a Vacation Bible School van driving down his dirt road neighborhood on a humid summer morning. At five years old he accepted the invitation of a friend and accompanied her to church for the first time.

Jonathan has been living under the radar for the past 15 years as an undocumented immigrant. His parents had come to the United States on a work Visa but had temporarily left him with his grandmother until they could establish themselves.

Jonathan has been living under the radar for the past 15 years as an undocumented immigrant. His parents had come to the United States on a work Visa but had temporarily left him with his grandmother until they could establish themselves.

If they had known at the time, they could have brought him and established his residency. But instead, while living in Moultrie, his parents eventually saved and scrimped to pay a coyote — an individual who specializes in human trafficking — nearly $5,000 to sneak him into the country from Mexico. It was extremely risky and a high price to pay to reunite the family. Many such children die en route, suffocating in packed trucks with little ventilation or dying in the desert.

Jonathan was a fortunate one.

His parents are hard-working people, seeking the American dream through low-paying jobs that are plentiful in south Georgia. So Jonathan, from the first day he enrolled in a Moultrie kindergarten without any paperwork, became an undocumented immigrant.

That designation and a change of administration in Washington has placed him at the heart of a national debate. The focus is what to do with children who grew up under the radar and who face deportation to a nation they never knew.

Children from many nations face possible deportation. Those nations could include any place where parents struggle to raise their children in a safe environment.

Because Congress didn’t act on the legal status of the children, President Obama created the DACA program as a Band-Aid, subject to renewal. On Sept. 5, President Trump cancelled the program, giving Congress six months to provide a solution.

For the children, the threat of being removed from their families is once again a reality.

Those who file their paperwork by Oct. 5 and are approved have a two-year extension against deportation. When their deferment expires they can be deported. Those who do not file can be deported immediately.

Members of Memorial Baptist Church in this county seat town of 15,000 are working to stand in the gap, helping those eligible with the paperwork. They are working to keep families together as allowed by law — until the law says otherwise.

Nothing is guaranteed during the next six months of twilight that Congress has to create a comprehensive immigration plan. If it fails to act, current immigration law will continue to impact those families.

That is where Jonathan and the church fit into the picture.

Jonathan, now 17 years of age, was born far away on Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. When he stepped into that Vacation Bible School van he knew very little English — but he and his parents trusted the church down the street.

Coming to faith at a Moultrie Church

“I didn’t know anything about Jesus or God but those people at the Baptist church saw to it that I had an opportunity to hear the Gospel,” he said. One person in particular, Brenda Arnold, took him under her wing and taught him beginner’s English. Arnold is a school teacher, heads the Literacy Missions outreach at the church, and serves as director of the church’s Woman’s Missionary Union.

Little did Jonathan know that not only would he eventually come to faith, but that VBS encounter would be the foundation toward building the wall against deportation.

On a recent Thursday night Brenda and her husband Mike — who drove that van — worked to help Jonathan fill out the eight pages of paperwork to renew his DACA status. In a break from the paperwork he stopped to reflect back over the impact the church has made — and continues to make — on his life.

The lettering on the church sign out front says, “Where Everybody is Somebody and Jesus Christ is Lord.” To Jonathan that means he is somebody and now, Jesus is his Lord.

For thousands of undocumented immigrants like the Cervantes family, Memorial Baptist Church is a beacon of hope. Through its Literacy Missions ministry, these would-be Americans are learning how to speak English, move up the socio-economic ladder, start their own businesses, and for many, reach their dream of American citizenship. Some DACA recipients are now in their early 30s, working below the radar in low paying jobs. Others are in elementary school.

Yet just like Jonathan, they are caught between two worlds.

“As far as Mexico is concerned, I ceased to exist at three years old when I came to the States. My parents were fleeing poverty, gangs and drug cartels who controlled much of the country,” he explained.

“They have told me stories of how they had to lock their doors at night to prevent criminals from entering, and how gunshots would awaken them from their sleep. They wanted a better life, so they received a work permit to come to America,” he said.

As far as the United States is concerned, he doesn’t exist, either. There is no documentation of his entering the country, no dental record of having a tooth pulled. Nothing.

VBS record was the missing link

That is, until Mike, Brenda’s husband, opened the door to the church van and ushered him into VBS. Eventually Jonathan made a profession faith in Christ, as well as his parents. He entered the school system, living under the radar, and eventually moved on with his family who became involved in a Spanish-language church.

A few years passed and, as he became a teen, he learned that Memorial was helping individuals like himself complete DACA paperwork. And the church was providing the ministry at the cost of the applications fees and with free legal aid. That saved the teen at least $2,000 from charges of professional preparers.

He returned to the church and renewed his friendship with Mike and Brenda and others who took up the challenge to document his presence. Thus began a hard road to walk, completing paperwork that established residency as of June 2012 — the date when the Obama Administration began the program as well as Jonathan’s arrival to the U.S.

But the Arnolds eventually hit a dead end establishing those important qualification dates. The trail went cold. It began to look pretty hopeless until Brenda began to search those decade-old VBS records and miraculously found a photo of the young Jonathan. Jonathan’s picture and VBS Certificate provided the needed evidence.

Now Jonathan has a future in America — at least for the next two years.

Jonathan plans to attend Toccoa Falls College next fall and major in business. He hopes to one day start his own restaurant or other enterprise.

But if Congress does not take action, the clock will once again start ticking and when his DACA status expires in two years, he could be removed from college and deported back to a world that he does not know and does not know him.