MARALAL, Kenya (BP)–Slowly the crank goes round and round, generating electricity to start the machine. The people sitting around it stare — amazed — when the box “speaks.”

At first, they laugh nervously. Then a silence falls on the group as they listen to the box tell of a God they do not know.

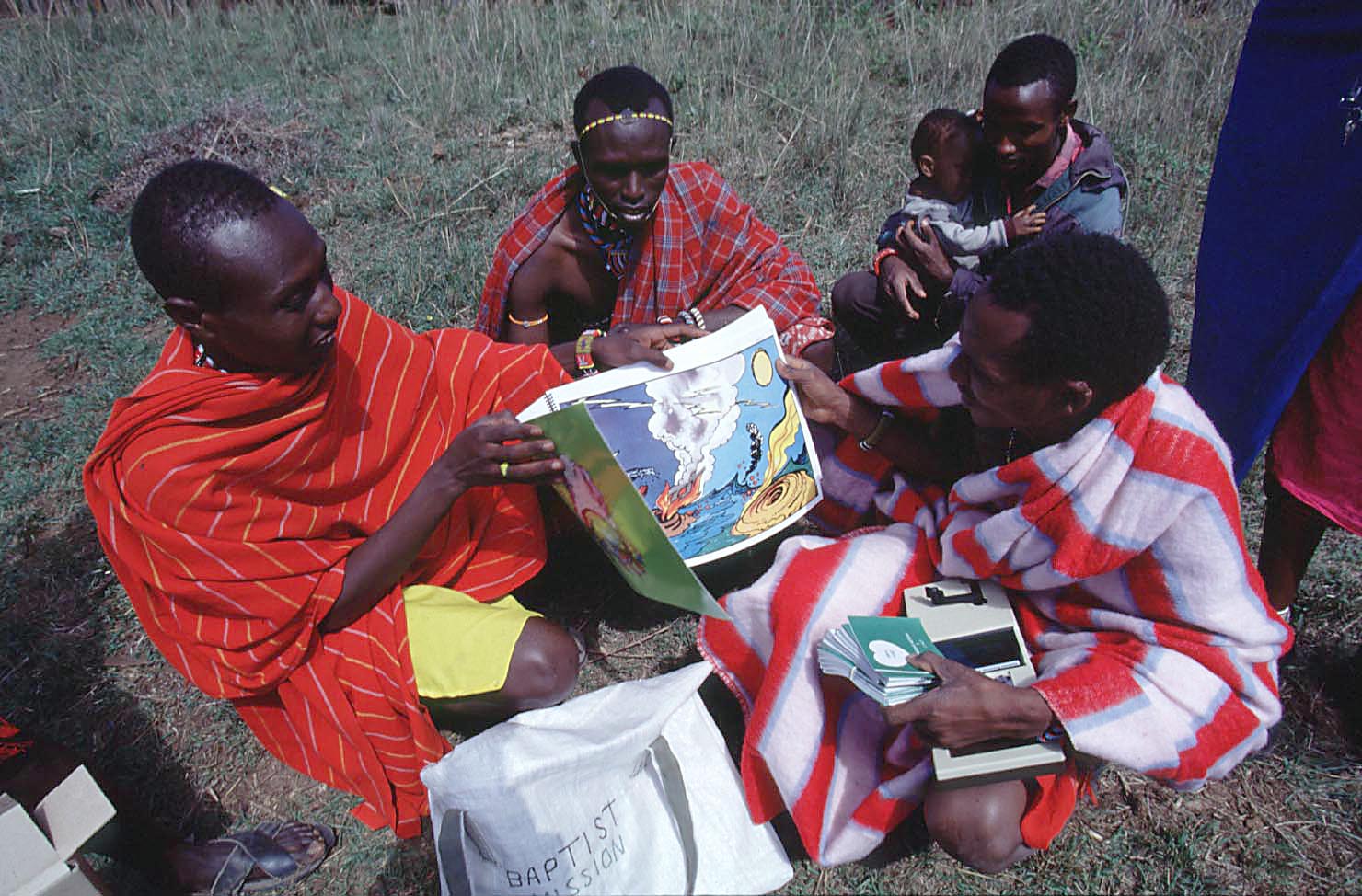

Don Dolifka, an International Mission Board missionary in Kenya, offers the hand-cranked tape recorder to a man sitting in the circle. He drops his club and spear to continue cranking. Soon, the group of 10 sits motionless, soaking in every word.

“They’ll sit like that, listening to the tapes, until midnight,” says Dolifka. “Tomorrow, they’ll do the same thing — only next time even more will show up to hear the box that speaks Samburu.”

Dolifka and his wife, Mary Alice, say this church-planting method has resulted in more than 150 “contact points” among the Samburu (Sahm-BOO-roo) people of northern Kenya. A year ago there were only 10 contact points — places, usually under a tree, where people gather to hear a lesson from the Bible.

The Samburu have not always been this responsive to the gospel. Things have come a long way since the Dolifkas began work with these nomadic cousins of the Maasai people in 1990.

The average Samburu prays to a god every morning but does not have a concept of a personal relationship with God the Father or knowledge of Jesus Christ as Savior. The Samburu believe in an omnipotent and omnipresent god called NkAi.

“The danger we found is their beliefs are so close [to Christianity] that sometimes they don’t see the difference,” Dolifka observes. “We had to find a way to let them see and experience the difference Jesus Christ makes.”

Doors began to open with a project aimed at the most important thing in a Samburu’s life — cows. In Samburu culture, the number of cattle a man owns determines his wealth and status in the community.

The animal care project took shape after Dolifka noticed that 80 percent of sicknesses could be treated by someone other than a veterinarian. Three Samburu church leaders learned how to treat the ailments.

The main emphasis of the animal care project is God’s healing power. Workers carefully pray for each animal treated and thank God when one is healed. “The prayer has made a big difference,” reports George Lenguro, one of the church leaders trained to treat the animals. “People know it is not our medicine but God’s power. They saw that God was accepting our prayers, and they began wanting us to treat their animals.”

While the animal care project opened doors for sharing the gospel, the Dolifkas knew more had to be done.

For the Samburu to be reached, they needed the gospel in their own language. Neither of the Dolifkas, however, spoke Samburu.

The solution came three months later when Lenguro approached the missionaries and said God wanted him to translate the Bible. Lenguro, an elder in the tribe, began translating the Gospel of Luke in his mud-packed home.

It was about this time the Dolifkas began “storying” the Bible by using hand-cranked tape players. The cassettes explain the Bible chronologically.

“The people would rather listen to the tapes than me,” Dolifka says. “That’s because this box speaks their language.”

The Samburu play these Bible lessons before most community meetings. Young men listen to them while watching the herds of cattle. Women and children listen at the water source. Elders listen while sitting in the afternoon shade.

“The people see this is pure Samburu. It is God’s Word, and he is speaking to us in our language,” Lenguro says. “Because God is speaking to us in Samburu, the people feel this must be an important message, and they must listen and learn.”

“This rapid growth is not something we did,” Mary Alice Dolifka says. “It is the direct result of God working in the lives of the Samburu.

“They have taken the gospel message seriously and spread it everywhere they go. They feel that everyone needs this message, and it is their duty to share it.”

How far are the Samburu willing to go to share God’s Word? Two Samburu men walked 12 hours down the rough terrain of East Africa’s Rift Valley. Neither knew if he would come back alive.

One was a local chief and elder, the other a “morani,” a warrior appointed to protect the villages. They had heard a neighboring tribe, the Pokots, had problems with their cattle and went to offer help.

Historically, the Pokot and Samburu people are enemies and work hard at staying that way. But these two Samburu Christians wanted to share the good news of Jesus — even with their enemies.

The young morani, Dickson Lesiamito, took a tape recorder and tapes with Bible stories in the Pokot language. The two men treated the Pokot’s cattle, then walked back home.

Days later, Lesiamito was surprised by a visit from a Pokot man who had walked an entire day to find him. The man was sent by his village to bring back the same truth that had changed the lives of their neighbors.

“The Samburu have a saying, ‘Nkiiikwae ninye ng’oki,'” Lesiamito says.

“It means that if someone gives you a message and you deny to share it, it is a sin. So we must go wherever we can to tell the gospel message.”