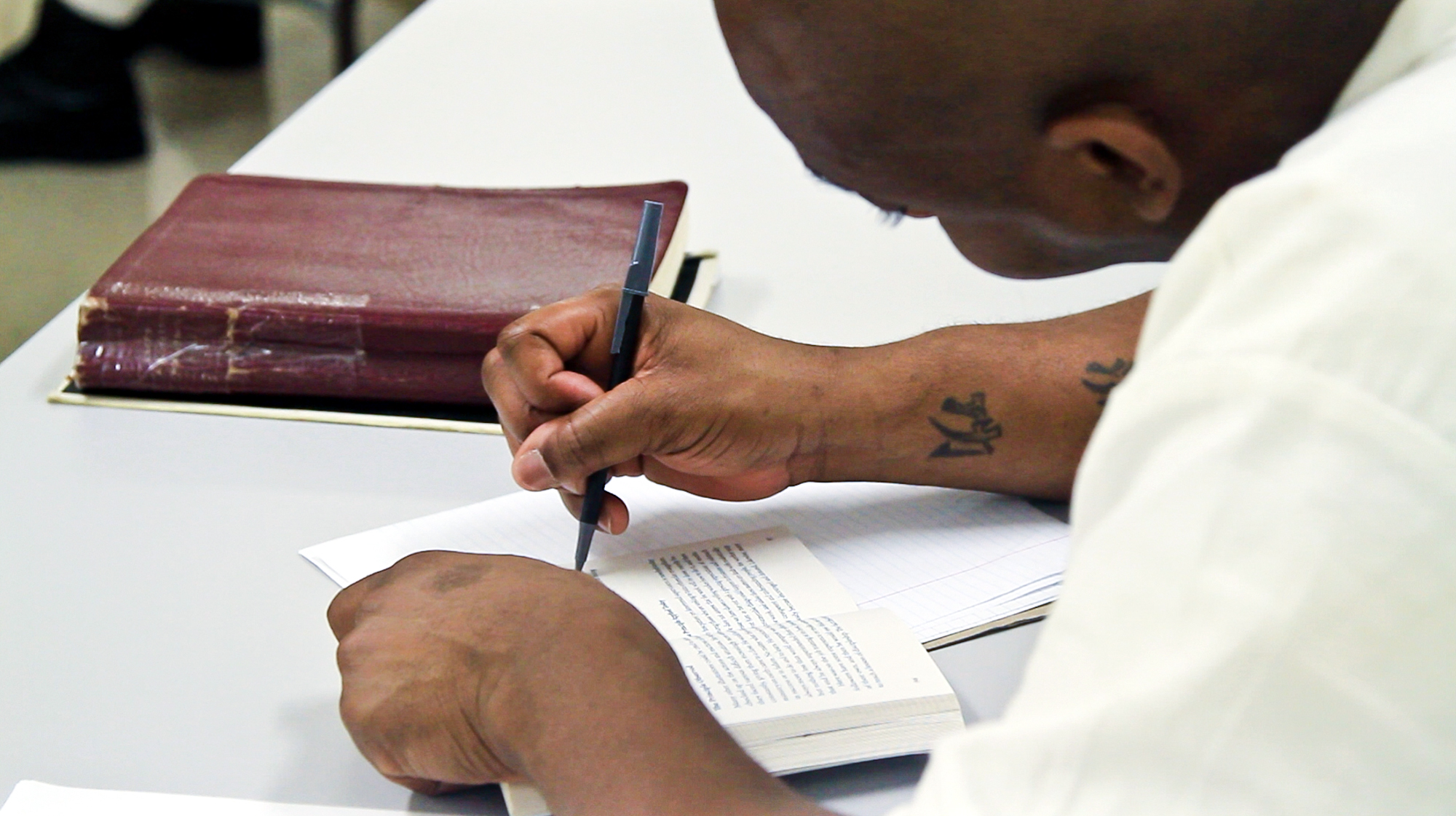

HOUSTON (BP) — In a cinderblock room with a concrete floor and metal bunk bed, no phones or computers ping or ding with text or Tweet alerts. For those serving time in prison, the onward march of technology could just as well be a lifetime sentence or two away. Instead, amid the unmuffled clang of heavy metal doors and the routine spontaneity of pat-downs and shake-downs, letter writing thrives as it did in the first century.

Stephen Presley, who is teaching an inaugural biblical interpretation class at a maximum-security prison near Houston, says the inmates’ familiarity with letter writing has given them a unique perspective on the epistles that comprise a large portion of the New Testament.

“They, in a very real and a very sincere way, understood what it would have been like for the early Christians to start to receive letters from Paul,” Presley said. “I think that [for] those of us who live in a world that’s dominated by email and controlled by other forms of technology, sometimes it’s hard for us to understand the genre of letter writing — the genre of the epistles.

“But for those who live in this world [behind bars], it was so easy for them to comprehend and to almost identify with the early church in the way they would have felt receiving these letters from Paul and how they would have treated the letter, perhaps, even in ways we don’t, in terms of reading it from start to finish, reading it closely and observing every word.”

Presley, assistant professor of biblical interpretation at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary’s Havard campus in Houston, said he had not anticipated the connection inmates in a new seminary extension at the Texas Department of Criminal Justice’s Darrington Unit would find with the apostle’s epistles until he saw the realization spark in their eyes as he began to discuss the letters the apostle wrote to the first-century churches.

“Their faces lit up … [when] they felt a sense of connection to the way that the early church communicated in ways that those of us who live in the free world don’t understand or don’t necessarily appreciate,” Presley said.

The similarities appear uncanny. Even down to the greeting, the inmates’ letters and the letters from Paul, which he, too, often wrote from prison, seem to almost mirror one another.

“Within the prison itself, they have a standard greeting,” Presley said in comparing the inmates’ letters to Paul’s, which follow a recognizable Pauline pattern. “Their standard greeting in the prison system is, ‘I pray this letter finds you in good health and in high spirits.’ It was interesting; none of them had actually talked about it, but they sort of all had taken on this standard format for letter writing.”

For the inmates, though, a letter is far more than a greeting or piece of paper or even the message written on the page. Presley said the men read and re-read their letters to extract every single bit of information they can. They pay attention to what the writer said and to what the writer left unsaid.

“When we read letters, sometimes we start in the middle; we go to Philippians, chapter three, and begin reading,” Presley says. “They read beginning to end many times over, and they spend time reading slowly. They don’t just read the letter quickly and try to move on to application. No, they spend time soaking up every single word, every single sentence, every phrase. It’s to the point where many of them would almost drive themselves crazy because they’d spend so much time thinking about the letter, they’d start to wonder what was happening back home. In fact many of them even carry [the letters] in their pockets almost as badges of honor.”

The inmates’ perspective opened a new line of thought for Presley in his study of the epistles that he otherwise might have missed in the hubbub of a text message- and email-driven world. Their connection to the epistles substantiated the importance of studying genre in the Scriptures and understanding the context in which the authors wrote the Bible under the Holy Spirit’s inspiration, Presley said.

“I think in the end it will kind of shape the way I teach writing in the future, because it’s such a great example,” the prof said.

The classroom exchange has also impacted the way the inmates are sharing, Presley said.

“Many of them have voiced that they feel more confident in handling the Scriptures than they did before,” he said. “They feel more confident about teaching other inmates. They are more passionate about teaching the Scriptures.”

Presley said one of his students has asked him for help interpreting the Gospels and parables for a sermon he wants to preach in the chapel. Another student found a Spanish translation of “Grasping God’s Word,” a book written by J. Scott Duval and J. Daniel Hayes which Presley uses in his class with the inmates. That student, he said, plans to teach the class to a group of Spanish-speaking inmates in the general population of the prison.

“We’re still beginning, but there is an excitement and a passion and a desire to see the love of Christ invade and take over the prison system,” Presley said. “They are excited; they are confident; they are passionate; they want to evangelize; and they want to see the love of God spread not only to Darrington but to other prisons.”

–30–

Sharayah Colter is a writer for Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary (www.swbts.edu).