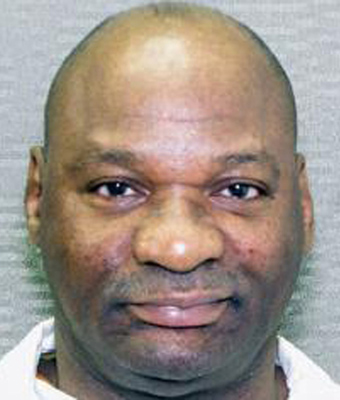

HOUSTON (BP) — Bobby James Moore got the death penalty for a murder he committed in 1980 at a Houston supermarket. But 36 years later, he apparently has a new argument: He is intellectually disabled and cannot be executed under a 2002 U.S. Supreme Court ruling. The Supreme Court heard his case at the end of November.

Moore was 21 when he and some friends decided to rob Birdsall Super Market. His job was to stand guard with a shotgun. Things did not go as planned. Almost immediately after two clerks in the courtesy booth learned they were being robbed, one of them screamed.

Moore pointed his shotgun at the second clerk, a 72-year-old man named James McCarble, and shot him in the head. McCarble died instantly.

Police caught up with Moore 10 days later at his grandmother’s house in Louisiana, where he confessed to the crime.

In 2002, the Supreme Court ruled executing the mentally disabled violates the Eighth Amendment prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. But the court left it up to the states to determine mental ability within certain parameters.

During oral arguments in November, lawyer Clifford Sloan cast Texas as an oddball state that uses something other than current clinical standards to diagnose intellectual disability — a 1992 definition along with other factors thought up by judges, not scientists.

The Texas appeals court said Moore had abilities that showed he was not so intellectually disabled as to be exempt from capital punishment. Both sides agreed Moore had a terrible childhood. He dropped out of school in ninth grade. His father beat him. He was kicked out of the house at 14. He had four felony convictions by age 17.

“At the age of 13, Mr. Moore did not understand the days of the week, the months of the year, the seasons, how to tell time, the principle that subtraction is the opposite of addition, standard units of measurement. And there are numerous other deficits like that that are undisputed,” Sloan said.

Justice Stephen Breyer had his doubts about whether the Supreme Court could establish a consistent standard for judging mental ability.

Texas Solicitor General Scott Keller argued the state’s criteria for intellectual disability is consistent with Supreme Court precedent as well as clinical standards. He also noted the legal finding of intellectual disability is different from a medical diagnosis.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg had a concern of her own about letting states set their own standards: “Isn’t making it discretionary a huge problem in this area, because if you let one trial court judge apply it and another one doesn’t have to apply them, then you’re opening the door to inconsistent results depending upon who is sitting on the trial court bench, something that we try to prevent from happening in capital cases.”

The current justices are divided on the much more basic question of whether the death penalty is constitutional at all, for anyone. Breyer is a frequent critic of capital punishment, as is Justice Sonia Sotomayor.

In 2014, the court struck down Florida’s law that said if an inmate’s IQ is over 70, evidence of other intellectual disability need not be considered.