[1]

[1]

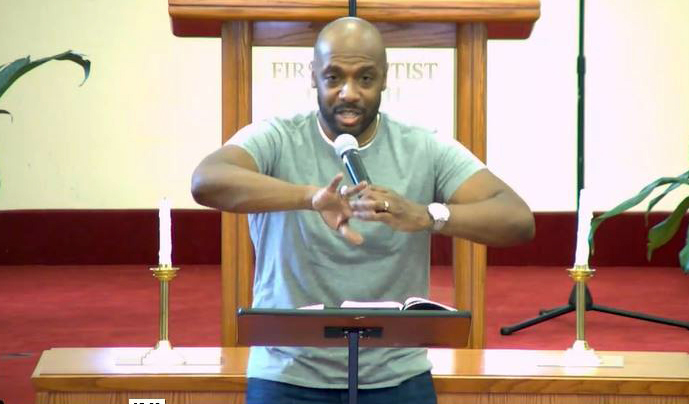

Eric Hankins (left), pastor of First Baptist Church, and Andrew Robinson, pastor of Second Baptist Church, have fostered healing between their churches in Oxford, Mississippi. Photo by Kevin Bain.

When First Baptist Church in Oxford, Mississippi, passed a resolution apologizing for its 1968 decision to exclude African Americans from worship services, it opened the door for racial reconciliation in its city.

"I had never seen a church or any organization move that seriously toward repentance and then apologize without any excuse," said Andrew Robinson, pastor of Oxford's historically black Second Baptist Church, a National Baptist congregation that accepted the apology and granted forgiveness.

Since the apology—which was reported by Memphis and Tupelo news outlets—First Baptist has participated in a community-wide interracial worship service, talked with local black congregations about how to partner in evangelism and ministry, and experienced moments of personal reconciliation between white and black believers.

There have been "amazing moments of reconciliation and forgiveness," Eric Hankins, pastor of First Baptist, said.

"We have the opportunity to now bring the redemption of Christ to bear in this situation," Hankins said. "The bottom line is that something has been done that is wrong. We've recognized it, and we're going to leave our gift at the altar until we go get this right so we can be correct in our worship. That's the appropriate response to a sin of the past."

The resolution says that First Baptist "declare[s] as utterly sinful the vote in April 1968 to exclude African Americans from worship." The apology "unequivocally denounce[s] racism in all its manifestations as a sin against Almighty God."

Although the 1960s in Oxford were an "extremely difficult" time, according to the resolution, "such difficulties in no way excuse what was done."

The resolution continues, we "repent . . . with our whole heart. We seek the forgiveness of the Lord and of African Americans who were and are still hurt by these things, and we hope they will extend such forgiveness to us."

Robinson told his congregation about their "obligation and opportunity" to extend forgiveness, but he did not coerce them to accept the apology.

"When we actually had the meeting to hear the resolution that was made by First Baptist, then our people readily forgave [because] it was coming from a church that didn't have to do this," Robinson said. "There was a sincere effort made by the church to repent of their sin."

Hankins, 42, arrived at First Baptist in 2005 and occasionally heard older members say the church had been on the wrong side of civil rights issues. But it wasn't until late last year, when deacon emeritus Sylvester Moorhead gave him a copy of deacon minutes from 1968, that Hankins got the full story.

Realizing some African Americans would be testing whether they could be admitted to various churches across the South, Moorhead moved that the deacons recommend an open-door policy for worshippers of all races, and despite some opposition the recommendation was approved by the deacon body.

When it came before the church though, it was voted down on a secret ballot in a business session after a Sunday morning worship service.

In the succeeding years, First Baptist used the vote as a basis for denying blacks access to its resources and facilities. One time it refused to host a communitywide prayer event because blacks would be in attendance. Another time, the church would not let its bus be used to transport black children to a backyard Bible club.

But by the mid-1970s, blacks began to attend worship, with the first African American joining in 1980 and the church enjoying increasingly warm relationships with blacks in Oxford. Still, the vote not to welcome African Americans had never been overturned.

So Hankins worked with the deacons to craft a resolution nullifying and apologizing for the 1968 decision. He also preached on corporate repentance and gave the church body opportunities to ask questions and offer amendments to the resolution. On July 21 the church adopted the resolution with more than 600 members voting for it and only four voting against it.

"It was high time," Moorhead, 93, said of the church's apology.

Hankins is quick to point out that not everyone in the church was on the wrong side of civil rights issues in 1968. Moorhead, for one, came to Mississippi in 1949 to serve as a professor of education at the University of Mississippi. He and his wife were shocked by the racism they saw and considered leaving the state before deciding to stay in an effort to influence others. Moorhead became dean of the university's school of education in 1960 and was instrumental in bringing black professors onto the faculty.

Several members of First Baptist helped make public school integration in Oxford one of the smoothest such efforts in the South, refusing to start private schools for white students to maintain segregation, according to Hankins.

Nevertheless, corporate repentance was required, he said. Hankins taught the church that sin has ongoing consequences in a community and must be repented of, even after those most responsible for it have died. In 2 Samuel 21, Israel was experiencing a famine because Saul had broken a covenant with the Gibeonites. Even though Saul was dead, David led the nation in making atonement in order to end the famine.

"David doesn't say, 'I didn't do that. It was Saul. That was not my generation. That's the previous generation,'" Hankins said. First Baptist stands "in continuity as one body" and must repent of the church's past sins.

Robinson said the apology "told those of us in the African American community that there are people who actually want to sincerely deal with racism."

When white Christians talk about racial reconciliation, some African American believers "back away from the table" because they have seen whites use supposed reconciliation efforts merely for political gain or to "touch up" their image, Robinson said.

But he said First Baptist's apology was different.

"We're talking about a church that is a powerful church and doesn't have to apologize," Robinson said. "It's going to have its reputation in the community, so it didn't have to do that. But they did that, and they showed that act of humility. It was done with such sincerity that it's hard for anybody to deny.

"It's hard to have a national conversation about racism," Robinson said. "It's something that needs to be done on a local level and in each community if we're going to get any real progress."

Robinson said that if more churches with racist pasts followed First Baptist's lead, hearts of lost African Americans might open to the Gospel.

For some blacks, First Baptist's repentance "will enable them to let go of some of that pressure that keeps their hands closed or their hearts set against the possibility of being witnessed to by white or black pastors. I do believe that when people see acts of repentance, acts of kindness extended such as this, it speaks volumes," Robinson said.