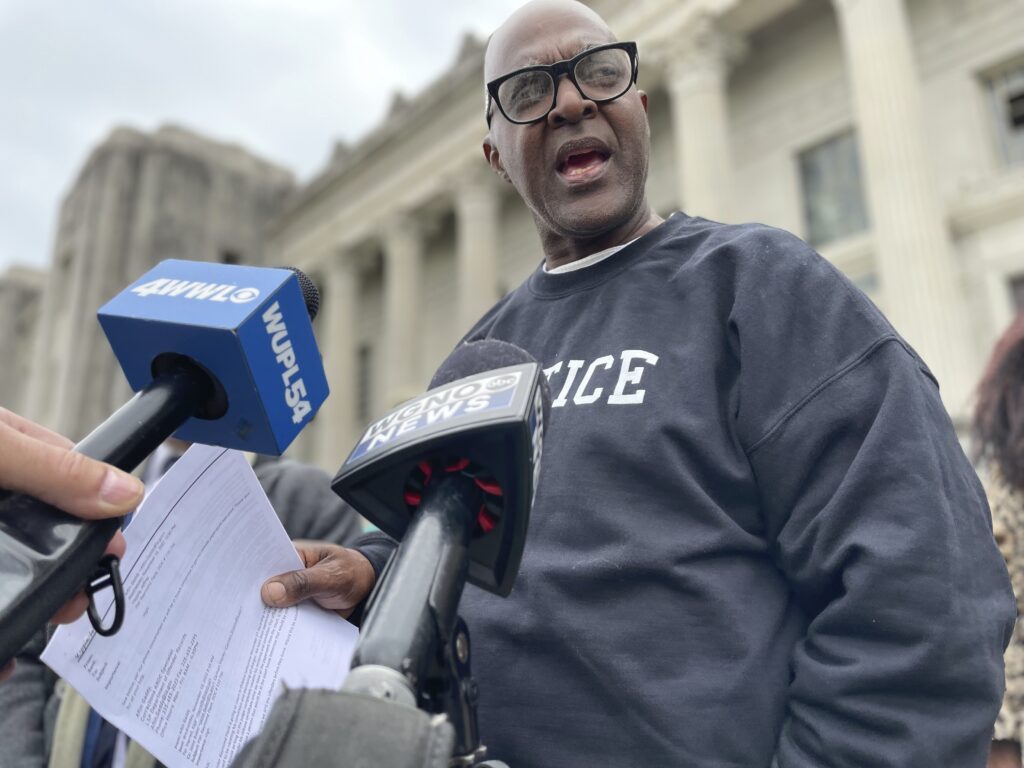

SAN ANTONIO (BP) – One year ago today (Nov. 17), Raymond Flanks was exonerated of a 1983 murder in New Orleans and was released from prison after nearly 39 years. He serves as an example of the need for criminal justice reform that reflects biblical justice, a Southern Baptist attorney said.

In 1985, Flanks was sentenced to life at hard labor with no possibility of parole at Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, where he entered the first class of New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary’s prison education program in 1995.

After earning an associate’s degree and then a bachelor’s degree, Flanks worked for years as a pastor to his fellow inmates, preaching sermons and observing communion using vanilla wafers.

On Nov. 17, 2022, Flanks was cleared of the murder and released from prison at age 59. He appeared on a panel at the Evangelical Theological Society’s annual meeting in San Antonio Nov. 15 with Matt Martens, an attorney, member of Capitol Hill Baptist Church in Washington, D.C., and author of the book “Reforming Criminal Justice: A Christian Proposal.”

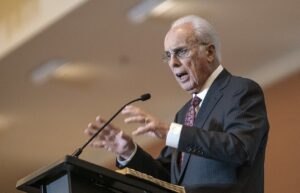

The core of biblical justice is to judge cases accurately, Martens told Baptist Press.

“Accuracy depends on due process. That’s the only means that we as fallible people, as finite people, have to achieve accurate results. It’s to develop and adhere to a process that surfaces and tests the relevant evidence,” Martens said.

The United States to some degree has lost its commitment to accuracy in criminal justice, Martens said, noting that since the development of forensic DNA technology in 1989, more than 3,300 people have been exonerated after having been convicted and imprisoned – sometimes for decades – for crimes they did not commit.

Since the death penalty was reinstated in 1976, nearly 9,000 people have been sentenced to death in the United States, Martens said. Of those, 195 later were exonerated – an error rate of more than 2 percent.

Most people wouldn’t get on an airplane with a 98 percent safe landing rate, Martens said, “so as a matter of Christian justice we shouldn’t subject our fellow neighbors to a justice system with an accuracy rate that we wouldn’t accept for ourselves. That is a failure to love our neighbors as ourselves.”

Martens opposes the death penalty as currently practiced in the United States.

“I accept the morality of the death penalty as an abstract matter. I accept that God has delegated to humans the authority to impose capital punishment, but He has done so under certain conditions and with certain qualifications,” he told BP.

The United States falls short today in part because the death penalty is not consistently administered with accuracy and impartiality.

“A death penalty system that is not accurate and that is racially biased is not a death penalty that lives up to Scripture’s demands,” Martens said.

Two of the causes, he said, are a failure to sufficiently fund defense counsel for the poor and a failure of courts to enforce the obligation of police and prosecutors to disclose evidence of innocence they possess.

“Of the 3,385 exonerations since 1989, about 60 percent involved police or prosecutorial misconduct, and yet there are almost no consequences for law enforcement officials and prosecutors when they engage in that misconduct,” Martens said.

“I think that’s a failure of Christian justice to hold accountable those administering justice. Government is permitted under Romans 13 to bear the sword, but they’re also held accountable to God’s justice when they bear the sword.”

To reform the criminal justice system, Martens advocates increased funding for defense counsel for the poor and imposing discipline on law enforcement officials who act unjustly in their administration of justice.

Whether such officials are intentional or simply negligent in their misconduct, Martens is concerned that “ultimately we’re not deterring it through accountability.”

To change the system, people can vote differently, Martens said.

“Criminal justice is one of the few issues on which you can be a single-issue voter,” he said. “Your local district attorney isn’t running on welfare policy or foreign relations or on the federal budget. Your local district attorney is running for election on one issue, which is criminal justice. It’s a unique opportunity to be a one-issue voter in what is a one-issue election.”

Voters can become informed about their district attorney’s positions and track record regarding false convictions and “instances in which his or her office has failed to hand over exculpatory evidence to a defendant.”

Martens also encourages people to view jury service as a stewardship and an opportunity to be part of administering justice according to God’s standard.

“It’s a very natural tendency to want to avoid jury service because of the inconvenience, but in a country where a jury verdict of guilty in a criminal case requires a unanimous jury, a single person who is committed to Christian justice, who is committed to due process and proof beyond a reasonable doubt, could single-handedly stop a false conviction,” he said.

As believers seek to love their neighbors as themselves, their obligation fundamentally is to seek their neighbors’ good, Martens said.

“Sometimes seeking the good of one of my neighbors could be seeking criminal punishment for him or her because he or she has committed a crime, but seeking the good of my neighbors requires that we judge their cases accurately so that the person being punished is the wrongdoer and so that the victim is actually having the wrong against them vindicated by punishment of the person who actually committed the wrong.”