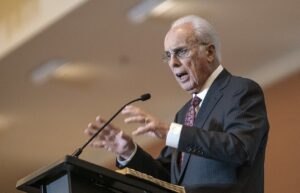

FORT WORTH, Texas (BP)–No one, including Jesus during his earthly ministry, has known if Christ will return in the year 2000 and the uncertainty should cause Christians to focus on duty and not dates, a church history professor maintained in a series of lectures on eschatology at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, Texas, Feb. 4-5.

“If we knew for sure, do you think we’d do our duty?” asked Timothy Weber, professor of church history at Northern Baptist Theological Seminary, Lombard, Ill., during Southwestern’s Day-Higginbotham Lectures.

The task for Christians, Weber said, is to keep on doing “the regular stuff.”

“You carry out your calling. The question is not when, but how you are living up to your calling. Are you redeeming your time?” he asked.

Referring to Matthew 24:36, Weber supported his contention that Christ’s return was an event that not even the Lord himself knew while he was on earth.

The passage quotes Jesus as saying, “No one knows about that day or hour, not even the angels in heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father” (NIV).

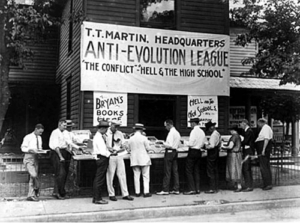

Some Christian groups believe the end of the millennium will mean the end of the world, Weber recounted, while others try to figure out the date of the Lord’s return by “millennial arithmetic.”

“These kinds of speculations are in a long, long line of date-setting,” Weber said, noting that for 2,000 years people have tried to predict Christ’s return, offering years like 1260, 1844, 1914, 1975 and 1988.

Jesus’ disciples, as Matthew records, wanted to know when the Lord would return and when the end of the age would be, to which Jesus replied that no one knew, not even himself.

Acknowledging the disciples’ question still persists, Weber also noted how the questioning is turning into anxiety for some people as the year 2000 approaches and how Jesus’ answer should help alleviate concerns.

“If Jesus doesn’t know, you can’t know either and you shouldn’t worry about it,” Weber said.

While giving his disciples a general picture of events that must occur before the end comes, “Jesus gave orders to the disciples not to set dates, but to do their duty,” Weber said.

In a second lecture on Baptist approaches to eschatology, Weber noted that Baptists do not have one singular doctrine of end times although the three main schools of thought — pre-, post- and amillennialism — that have developed center around Revelation 20:1-10 and Jesus’ millennial reign.

“Eschatology is not one of those things Baptists have been willing to define carefully,” he said.

Weber recounted eschatological trends in the church that began as premillennial and became amillennial around the time of Augustine in the fourth century. The trend was postmillennial during the 18th and 19th centuries, but during this century, “Baptists have lined up all over the place,” Weber said.

Weber noted that eschatology was not even mentioned in many of the great confessions of Baptists until the 1920s, and then only vaguely.

Acknowledging a diversity of thought within the three schools, Weber summarized the schools by saying amillennialists believe in the second coming of Christ, that Revelation is symbolic and that Christ will not reign on earth but is already reigning in heaven. Postmillennialists, he said, believe the world will gradually transform for the better over a 1,000-year period and the Second Coming will return after this millennium. And premillennialists believe the world will get progressively worse, Weber said; war, natural disasters, apostasy and persecution of believers will occur, and Christ will return suddenly and reign for 1,000 years before a final battle and final judgment.

The third lecture surveyed the teachings of three Baptist theologians active at the turn of the century: Augustus Hopkins Strong, William Newton Clark and E.Y. Mullins.

Strong, president of Rochester Theological Seminary, was one of the last major American theologians to espouse postmillennialism. Despite his belief that Christ would return after a thousand years of peace, he tried to make a connection with premillennialists, stating that Christ’s second coming was premillennial spiritually, but postmillennial physically and visibly.

“Strong was always looking for a way to split the difference,” Weber said. “He was a man in the middle.”

Not so his contemporary Clark, Weber said.

Clark, a leading Northern Baptist evangelical liberal and professor of theology at Colgate University, was committed to higher criticism and religious experience as the ultimate arbiter of religious truth and did not accept biblical inerrancy, referring to the Bible as a “source of theology,” not the final word on theological matters.

Referring to millennial approaches as “unhelpful,” Clark maintained that the texts teaching Christ’s return were holdovers from Jewish apocalyptic texts and a concession to the first-century audience of the gospel.

He believed the second coming took place at Pentecost and is continuing to occur. He did not expect any visible return of Christ and held that God’s spirit is working to advance his kingdom in human history. Clark said that resurrection and judgment occur at death for each person.

Mullins, former president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, Louisville, Ky., remained an “agnostic” over whether there would be a millennium, though he did believe in a literal and visible second coming, which Christians should await eagerly.

The Day-Higginbotham Lectures have been presented at Southwestern annually since 1965 by a scholar in a theologically related discipline.