DALLAS (BP)–Participants at a bioethics conference in Dallas tried to imagine what it was like for a local family to hear the news that their 8-year-old son had little chance of recovering from stroke-inducted brain damage.

During the “Cutting-Edge Bioethics: Human Life on the Line” conference at Criswell College, a local hospital chief of staff read the grim medical record as a panel of doctors and ethicists put themselves in the role of helping the family evaluate whether to keep the boy on life support.

Later in the discussion, the panel gained a real-life perspective on their counsel.

“The family was briefed on the alternatives and a very poor prognosis with no hope of recovery,” the doctor stated, referring to the medical assessment a day after the boy was admitted to a pediatric intensive care unit. “The suggested choices were long-term care or to plan a funeral as there was nothing continued medical care could offer at this point with extensive and irreversible damage to his brain.”

The previously healthy boy was diagnosed as being in a state of diabetic ketoacidosis, disoriented with cerebral edema. Early the next morning the boy had a massive stroke in the brain stem at the base of his skull. “The bilateral nature of the damage to this patient’s brain and brain stem make recovery most unlikely from a medical perspective,” the doctor recounted from the records.

He was placed on life support systems and remained in a coma. Doctors told the parents that their son, if he survived, would be a vegetable for the rest of his life.

Oxford’s Whitefield Institute director E. David Cook spoke of the need for a family friend — a pastor or another member of the family — to help explain and mediate for the family. “My first concern would really be to find out how the family is responding to this kind of situation.”

Trinity International University ethics professor C. Ben Mitchell agreed for the need for someone to interpret the medical facts, bring in moral values and determine who serves as the appropriate decision-makers.

Christine Taves, a surgeon from University of Mississippi Medical Center, noted, “If this person were in his 70s or 80s, clearly a stroke carries a different prognosis than it does in a child. Children’s brains are pliable and have an ability to bounce back more than as we get older, we just don’t know.

“To say based on a CT scan that there’s irreversible damage when he’s still moving and reacting to pain is probably a little early,” Taves added, stating that it would be premature for an 8-year old 24 hours after admission to say, “We don’t have anything else to offer. Let’s stop.”

“It was too early to be so declarative,” reiterated Robert Orr, director of clinical ethics at the Center for Bioethics and Human Dignity and longtime physician. “If we make a decision now to limit treatment, that will ensure the patient dies. If we do not, we can almost ensure that the patient will recover, but in a severely debilitated position. So we have this time frame that it’s better to make decisions earlier if we’re trying to avoid long-term severe incapacity.”

Aware that he was assessing a real-life case, Orr added, “Sometimes the motivation is for trying to push things along faster. I’m not sure I always agree with that, but I think it’s part of the thinking.”

Returning to the case file, the hospital chief of staff read from a Jan. 12 record, two weeks after the boy’s admission to the hospital. “The parents have been very involved in his care and a family member [has been] present at his bedside twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week.”

Upon release from the ICU, the family immediately was presented with the only option of inserting a gastric feeding tube into their son. The procedure was stopped by the parents on the day of the scheduled surgery. After five weeks in the hospital, the boy was discharged to a pediatric rehabilitation hospital. His condition was described neurologically as “devastated, but stable.”

Taves said she tries to help families understand that it takes a week in rehabilitation for every day in ICU. And for children, she said, it is more difficult to relate prognostic indicators.

Cook praised a practice at Oxford in finding a support group of individuals who have been in similar circumstances, as well as providing a social worker to take the family to the rehabilitation unit to show the long-term care available. “I’d be looking for a care plan that would actually be comprehensive,” he said.

Mitchell spoke of the need for a moral diagnosis beyond the medical assessment. “What are the moral resources this family has to draw on when making a decision?” he asked, noting the importance of clinicians and other caretakers understanding the values of the family.

“In cases like this, often there is potential for communications breakdown with a lot of different kinds of terminologies, languages spoken, the whir of machines and flashing lights of monitors,” Mitchell added, describing a medical environment with which most families are unfamiliar. “There has to be some level of confidence in the people who are caring for your loved one. If that is clear, then we can begin to work at the other tiers of moral decision-making.”

After the panelists offered feedback, the hospital chief of staff began reading further from the record. Then all eyes turned to the youngster who was slowly walking into the room with the help of his family.

“Thank you for praying for me and I know God is healing me,” Jonathan Cooper told the panel and audience as they applauded the arrival of the boy whose case they had studied. “He’s helping me get better every day and I know that I have to go to therapy to get well and for me to get over this and I’m working real hard at that and He’s healing me every day.”

Jonathan’s mother, Kristi Cooper, told the panel, “I wish we had had doctors that were dealing with us that believed in their God as much as they believed in their medicine. I feel like if that were the case, we would have received different advice, different consultations.”

Instead, she recalled, “We were told that because of the injury he had, there was no guarantee there would be any quality of life.” She advised medical personnel to remember, “You are not just issuing a diagnosis, you are telling them about their child or mother or father or someone that they dearly love.”

Both parents recalled instances when they were told only one option remained when, in fact, other courses of treatment were available. “Not every situation is by the book,” Lamar Cooper Jr. said.

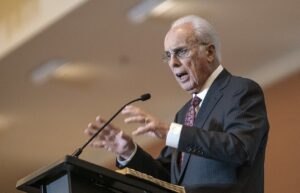

Jonathan’s grandfather, Criswell College Executive Vice President Lamar Cooper Sr., told of movements he saw his grandson make while comatose that were dismissed by nurses as primal responses. After Jonathan smiled the first time while still in a coma, Cooper soon learned of the prayer of a friend who had asked God to give the family a sign of encouragement by letting the boy smile for them.

Throughout the experience, the Coopers kept friends and family informed through a website at www.jonathancooper.org where readers could follow a daily accounting of the up and down struggle. Early on, the family expressed appreciation to the 140 people who poured into the House of Prayer at Lakeland Baptist Church in Lewisville, Texas, where Jonathan’s father serves as director of communications.

Over the course of the next few months, Jonathan regained consciousness and began eating on his own after moving to a new pediatric rehabilitation center. “I can’t tell you how awesome it is for us to see Jonathan eat by mouth,” one parent related in the online journal. “If you recall, this is now the second thing that the neurologist said he would never do. Our God is an Awesome God!”

After seven weeks of being unable to express himself verbally, Jonathan told his family, “I want some milk,” and then, “I want some more milk,” and even, “I want some chocolate milk.”

Within a week he was talking throughout the day, calling each member of the family by name. By the end of two months he was able to have a hot dog, French fries and Diet Coke at Sonic. By Easter he was able to leave the hospital and go to church with his family.

The online journal described the outing. “When we got there, Jonathan was able to walk with his walker across the stage and stand before our church family who has so faithfully prayed for us, loved us and supported us as though Jonathan were their own child. He spoke with a clear voice, ‘Thank you for praying for me. I know God is healing me. Again, thank you for praying for me. I will see you in a few weeks.’”

Even earlier than expected, Jonathan was released from the rehab facility after 14 weeks away from home. With therapy, he has continued to make marked progress, gaining strength to increase his mobility. Prayers continue for the healing of his brain, vision and diabetes. On May 1, Lakeland Baptist welcomed him back and invited his father to share some of what God taught their family through their journey of prayer and faith.

“As far as I’m concerned, what you’re looking at here is an unexplainable medical anomaly, but a 100 percent visible answer to prayer,” Lamar Cooper Sr. told the conference at Criswell College. With tens of thousands of e-mails received at the website where Jonathan’s progress was recorded, Cooper said it was a testimony to the power of prayer.

“The final word is not always the final word,” Cooper said. “In the final analysis He alone should have the final word. On end of life issues, let’s be sure He gets the chance. This family gave God a chance and God responded.”

–30—

Tammi Reed Ledbetter is a contributing writer to the Southern Baptist Texan, newsjournal of the Southern Baptists of Texas Convention, online at www.sbtexas.com.