LIVINGSTON, Texas (BP) – About 200 of the inmates at the Allan B. Polunsky Unit – a Texas Department of Criminal Justice maximum-security prison near Livingston – are housed on Death Row, where prisoners typically spend 23 hours a day in a small, single-occupancy cell.

‘Broken men become whole’

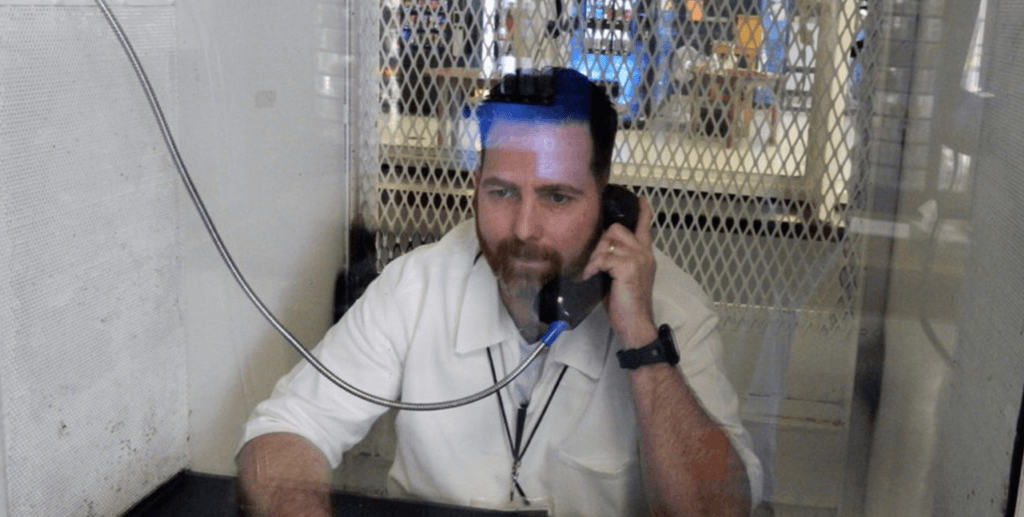

But Terry Joe Solley, an inmate in the general prison population who devotes 12 to 14 hours a day visiting those otherwise-isolated prisoners, is committed to turning Death Row into “Life Row.”

“We introduce them to the one who can give them spiritual life. They find spiritual life in a place where they have come to die,” Solley said. “On Life Row, broken men become whole.”

Solley is one of six field ministers at the Polunsky Unit. Field ministers are inmates who have completed a Bachelor of Arts in biblical studies degree program, offered to men at the Darrington Unit in Brazoria County (renamed the TDCJ Memorial Unit last year) and to women at the Hobby Unit in Falls County. They receive certification as field ministers after receiving specialized training from the Heart of Texas Foundation Field Ministers Academy.

The two field ministers at the Polunsky Unit – Solley and Hubert “Troop” Foster – are assigned specifically to Death Row where they “are basically pastors to the Death Row population,” Chaplain Joaquin Gay said.

Field ministers “are the heart of our Death Row ministry at Polunsky,” Gay said. The field ministers have earned the trust of men housed on Death Row – not only teaching classes and conducting worship services, but also visiting the inmates daily, praying with them and being on call 24 hours a day, seven days a week, he explained.

The field ministers – who are permitted to enter Death Row without being escorted by a correctional officer – often are awakened in the middle of the night at the request of a condemned inmate who wants to talk.

Some Death Row inmates grow so despondent, they consider suicide, Solley said.

“I’ve had men give me the razor blade they were going to cut themselves with,” he said.

“These men are sons, husbands and fathers. We often lose sight of that. … I want the men on Life Row to see themselves for who they are – people created in God’s image, not just a messed-up life. It’s not about what you did. A single moment doesn’t define us. It’s about who you are.”

‘I wanted to please my father’

Before he surrendered his life to Christ, Solley spent much of his incarceration in administration segregation units – solitary confinement reserved for prisoners considered a safety risk to other inmates or prison staff.

“I spent years on ad seg in a 5-by-9-foot cage, carrying a lot of guilt and shame,” he said. “So, when I talk to the men on Death Row, they know I can relate to them.”

Solley recalled attending First Baptist Church in Lafayette, La., faithfully with his mother from age 7 until he was 14 years old. At that point, his father – who went to prison when his son was 6 years old – released and came back to his family.

“That’s when he took me to do an armed robbery with him,” Solley said. “I wanted to please my father more than anything.”

At age 18, Solley went to prison, where he served 10 years, seven months and 23 days before being released. Once he returned to the free world, he married, had a child and began a productive life until his father “showed up again,” he said. On March 25, 2006, Solley committed a bank robbery.

“I became everything I said I wouldn’t become,” Solley said.

‘Now I am stronger in the broken places’

During the time he was held in a county jail, before he was convicted and sent to state prison, Solley returned to the faith his mother had tried to teach him and accepted Jesus as Lord of his life.

“God put together the pieces of a broken life, and now I am stronger in the broken places,” he said.

In prison, after he renounced his former gang membership and proved his trustworthiness, he was allowed to enter the seminary program at the Darrington Unit.

“My family was against it, because my dad was at the Darrington Unit,” he said. Initially, Solley wanted no contact with his father, but he eventually agreed to meet him in the prison chapel. His father began attending chapel services regularly.

“He would watch me. One day he said, ‘There’s something different about you,’” Solley said, “I told him, ‘Jesus is now Lord of my life.’”

In April 2012, Solley’s father asked his son to walk with him to the front of the chapel at the end of a worship service.

“He said, ‘I want to give my life to the Lord,’” Solley recalled. Two months later, Solley’s father was diagnosed with Stage 4 liver cancer. He died in September 2012.

“Before he died, God mended our relationship,” Solley said. “For the first time, our relationship wasn’t about pistols and ski masks.”

First faith-based designated units on Death Row

After completing his degree and receiving additional training as a field minister, Solley spent 15 months at the T.L. Roach Unit in Childress before he was invited to transfer to the Polunsky Unit to serve Death Row.

“I didn’t know what to expect,” he confessed.

But the first inmate he met on Death Row was John Henry Ramirez, who had become a Christian through the prison outreach ministry of Second Baptist Church in Corpus Christi.

“We became fast friends and brothers,” Solley said.

Ramirez said the same thing about field ministers Solley and Foster.

“It’s a privilege to have somebody to confide in,” Ramirez said. “We’re not just spending time in our own heads 24/7. Sometimes, the field ministers listen to people rant. Sometimes, they cry. Regardless, they are there.”

Ramirez is among 28 inmates who are part of the first designated faith-based units on Texas Death Row.

“The faith-based program is an intensive, voluntary, 12- to 18-month program that seeks to provide men with a living area separated from the other inmate population that is conducive to change and designed to provide resident offenders with a curriculum of meaningful opportunities for personal growth and improvement,” Chaplain Gay said.

To qualify for the program, inmates must have a clean disciplinary record, and they need to submit a written request to the chaplain’s office. From those who apply, the chaplain compiles a list of inmates he recommends to the warden for a final security check prior to approval.

“The men who are selected to participate in the faith-based program are moved to an area of Death Row semi-separated from other Death Row inmates. The 28 men are divided up into two adjacent living areas that house 14 men each,” Gay explained.

“Our primary goal of the Death Row faith-based program is to help participants reach a point in their lives where they are truly repentant for their actions, seek forgiveness and find inner peace with God.”

Personally, Gay added, he wants inmates not only to experience the most productive and faith-filled lives possible, but also to “prepare them for the eternal life to come by offering them an eternal hope that is only found in Christ.”

‘Changed the dynamics of Death Row’

In recent months, 14 of the inmates in the Death Row faith-based program participated in a modified Kairos retreat. When a Kairos event typically is offered in the general prison population, the spiritual retreat lasts four days and involves volunteers who lead small-group discussions and worship services and who pray individually with inmates.

A dozen certified volunteer chaplain’s assistants, two field ministers and the chaplain led the Texas Death Row event. The retreat followed a compressed schedule, with inmates remaining in their cells, listening to speakers and musical worship leaders on a sound system at the end of the cell block.

“Over the course of two days, 30-minute talks were given on subjects ranging from forgiveness to being part of a church community,” Gay explained. “After every talk, a [certified volunteer chaplain’s assistant] placed a chair directly in front of two cells for a small-group discussion.”

Beyond the Kairos event and the programs offered specifically for the 28 men in what inmates sometimes call “the God Pod,” other Death Row inmates and prisoners in the general population can take courses offered on “The Tank”—a low-power, prisoner-operated radio station—and listen to broadcasts of other faith-based content.

Taken together, the “God Pod,” the field ministers, religious radio content and other faith-based programs dramatically have altered the prison—particularly Death Row, Ramirez said.

“It’s created a big sense of community here,” he said. “Before, we were all alone. It’s changed the dynamics of Death Row.”

He is not alone in that observation.

“All of the staff on Death Row have commented on how much the faith-based program has helped change the atmosphere on Death Row,” Gay said. “What was once a dark place has now become one of the unit’s beacons of light, as the Lord changes and transforms the men living there. None of the men in our Death Row faith-based program have had a disciplinary issue for some time now.”

Warden sees correctional work as a calling

Both Ramirez and Solley give credit to the prison administration, particularly Warden Daniel Dickerson.

“Correctional work is a calling more than a job,” Dickerson said. “There has never been one person that I have found that grew up wanting to be a correctional officer. Somehow, we are just led to this work, and when we actually understand the purpose and great responsibility, it becomes a passion.”

Dickerson believes strongly in programs to rehabilitate offenders.

“Society gets better when we do better. We can stop the vicious cycle of family members constantly coming to prison every generation if we put all of our faith and efforts into rehabilitating those incarcerated,” he said.

“It’s not an easy calling, but we have amazing people behind the walls giving it their all every day to provide public safety, which is not only keeping those incarcerated inside, but rebuilding them to enter into society in which they can be productive.”

Even for those who never return to society—including those who ultimately are executed—meaningful transformation can occur, Solley asserted.

“On Life Row, the gospel becomes real. If forgiveness of sins is really for all people, then it’s for them,” Solley said, pointing to the example of the thief on the cross next to Jesus who asked the Lord to remember him when he entered his kingdom. “The first man to come to faith in Christ was in the process of being executed.”