ANGOLA, La. (BP)–Heaven, hell, sin and redemption aren’t just words at Louisiana’s Angola Prison. Warden Burl Cain makes certain every inmate has the opportunity to know the transforming power of the Gospel.

Once called the bloodiest prison in America, the Louisiana State Prison at Angola now has a new reputation as a place of hope for more than 5,000 inmates who live out their life sentences without parole. Many inmates know they’ll leave the prison walls only when they die, yet despite their circumstances, there is joy in their hearts.

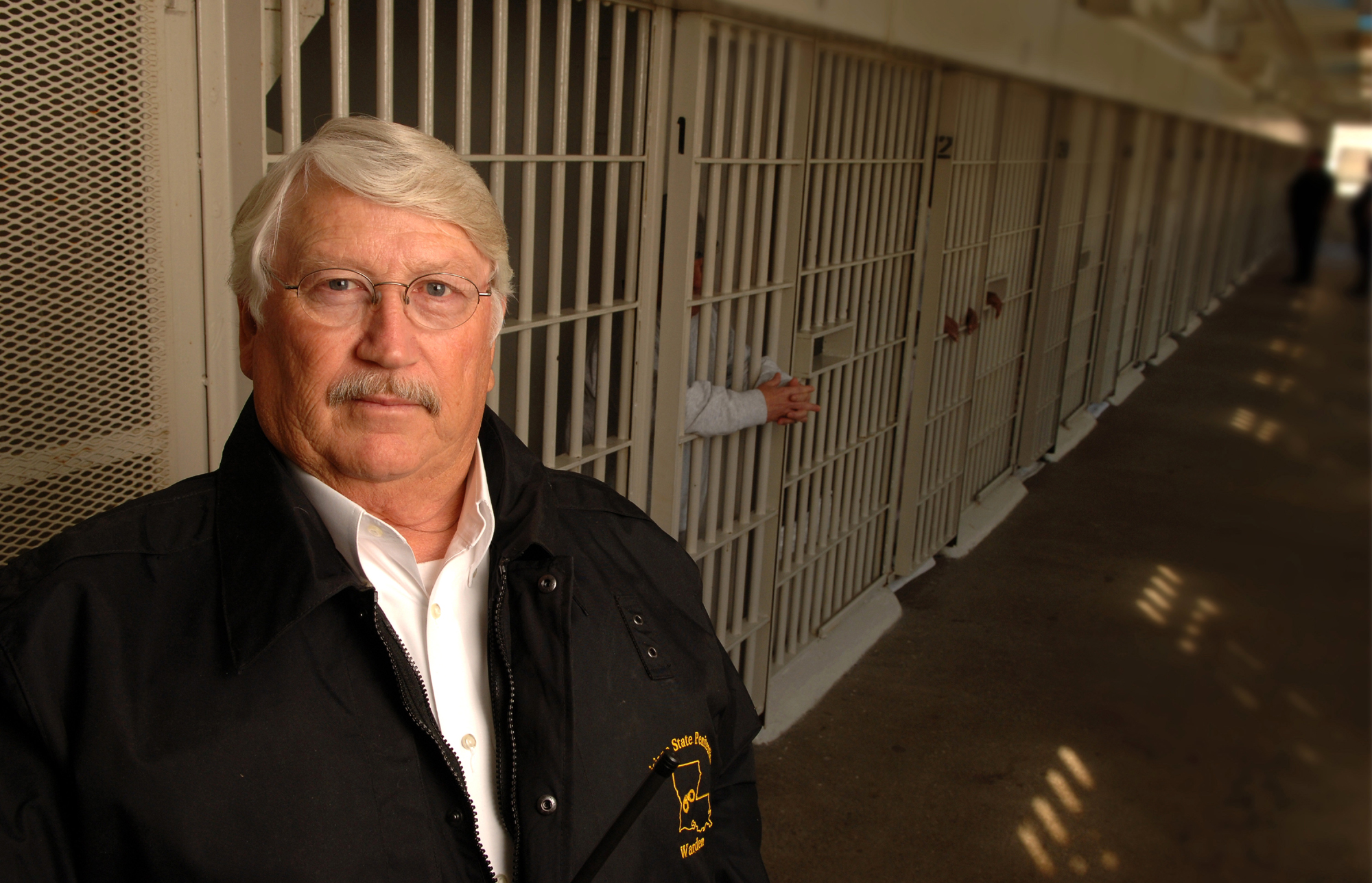

Credit for this unprecedented transformation is given to its one-of-a-kind warden, Burl Cain, who governs the massive prison on the Mississippi River delta with an iron fist and an even stronger love for Jesus.

The hallmark of Cain’s 12-year administration is his relentless effort to help each inmate discover value and purpose in life and experience true freedom of the soul, even when the inmate’s life is spent behind razor wire and guard towers.

“I truly believe these men can rebuild their lives — lives that have been shattered by awful crimes — if they embrace a genuine change of heart,” he explains. Cain wants the outside world to see that many inmates are being genuinely rehabilitated, and that perhaps a few could be released someday.

The stocky, unassuming warden can be a “good ol’ boy,” a down home Southerner spinning stories of life inside the sprawling prison. He is also fiercely locked on what matters most to him: his zeal for Jesus Christ, and his sense that God installed him as warden at Angola for His purposes.

Cain recalls the executions that changed the way he viewed prison life — and death.

His first execution twelve years ago was done strictly by the book. Cain had been on the job for only a few months in 1995 when the unpleasant task was scheduled. Cain planned to do his part in the procedure, nothing more, nothing less. A successful lethal injection execution would be one that went according to plan without a hitch.

Thomas Ward had been sentenced to die for murdering his mother-in-law. Cain viewed him as little more than a criminal whom society had ruled should die for his crime. “I didn’t worry about what he must have been experiencing in the hours before his death. I didn’t go to his last meal, and I didn’t share Jesus with him.”

When it was time for the court’s order to be carried out, Ward’s face was a mask of fear as the deadly fluids began flowing his veins. “There was a psshpssh from the machine, and then he was gone,” Cain recalls. “I felt him go to hell as I held his hand.”

“Then the thought came over me: I just killed that man. I said nothing to him about his soul. I didn’t give him a chance to get right with God. What does God think of me? I decided that night I would never again put someone to death without telling him about his soul and about Jesus.”

Feltus Taylor was the next inmate Cain was ordered to execute. He had been in the prison system before; he served his time and was released. Now he was back in prison, sentenced to die for shooting two restaurant employees, Keith Clark and Donna Ponsano, during an armed robbery after his release.

Taylor forced his victims to kneel in the kitchen’s walk-in cooler and shot them both in the head. Keith Clark survived, but was paralyzed from the neck down. Donna Ponsano died instantly. Taylor had spent years on death row as his attorneys fought to keep him alive, but eventually the appeals process ran out. The execution date had arrived.

The inmate’s family had come to visit on the execution day. As the appointed hour of death neared, Cain escorted them to a private waiting area and asked them to be strong. “Feltus needs to be as emotionally and spiritually ready as he can be in his final hours,” the warden said. He returned to the condemned man’s cell near the execution chamber.

“I met with Feltus, and we prayed together” Cain says. “When the time came, we took him into the chamber, and the guards prepared him for the execution,” Cain recalls. “I asked him if he had anything to say. He couldn’t hardly talk.”

One of the witnesses observing the scene through a window to the chamber was Keith Clark. Confined to a wheelchair, he had met earlier with the warden and talked about the inmate’s decision to commit his life to Jesus Christ. Keith Clark said something that amazed Burl Cain.

Cain stood next to Taylor as he lay strapped down on the execution gurney. He bent over for a whispered last-minute conversation. “I held his hand and told him to get ready to see Jesus’ face,” Cain remembered. “He looked up into my eyes and said, ‘Will you tell Keith Clark I’m sorry for what I did to him and Donna?’

“I nodded yes. Then, as his eyes began to close for the last time, I said, ‘Keith told me that he forgives you.’ He smiled, closed his eyes, and breathed twice. Then his breathing stopped.”

Warden Cain drove home that night, deeply troubled by the suffering he had seen that day. A woman in the grave, a man in a wheelchair, families destroyed. All because a selfish, sinful man wanted to steal a few dollars.

The correctional system had failed, he thought. The criminal justice system had failed, with tragic results. He vowed to do all in his power to transform the men under his charge. It would be worth the effort, even if one person was saved from being a victim of violent crime.

“I had come to realize that criminals are very selfish people,” Cain says. “They take your money, your property, anything they want for themselves. They sneak around, lie, steal, kill and do whatever they want. I could teach them to read and write and help them learn skills and a trade, but without moral rehabilitation I would only be creating a smarter criminal.”

Life in prison is a breeding ground for despair, “dying by inches,” Cain says. “I knew we had to do more.”

Cain knew three things for certain: society considers prisoners to be non-persons, a despairing prisoner with no hope is a dangerous one, but no one is beyond God’s love, forgiveness and redemption — not even hardened criminals.

Unless something changes in an inmate’s heart, he was likely to remain angry and bitter at the world that rejected him, Cain realized. He wondered how to reach those bitter, discarded human fragments.

Cain knew there was only one answer, one way to reach the offenders and convert them into men who genuinely wanted to make something of themselves in prison. He knew there must be a true conversion deep inside, touching an inmate’s very soul in that secret place where no man could fool himself. Cain believed moral rehabilitation had to occur in order for an inmate to lift himself beyond the jungle atmosphere that too often smothers a prison. The only way for true change was Jesus.

Cain and his team worked tirelessly to create a new prison, a better prison, a place where men sentenced to life imprisonment could choose to make lives and homes for themselves within the prison walls. Cain wanted an environment that was safer for the inmates and employees alike. He was determined to add value and moral responsibility to inmates’ lives.

A Southern Baptist, Cain invited New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary to launch a rigorous four-year college extension course for inmates who desired a college degree. The program is funded largely by private donations.

Every weekday, more than 100 men crowd into classrooms in a prison building to study the Bible and to take courses toward a college degree, accredited the same as one from Louisiana State University. Cain also began a certificate program for faith-based education, aimed at inmates who didn’t have a high school diploma or its GED equivalent. More than 100 inmates earned their certificate in 2006.

Each year, inmate seminary graduates who feel called to ministry are transferred “two by two” to other prisons in Louisiana to serve as inmate missionaries. They receive no special favors or time reduced from their sentences; they choose to serve God by sharing the Gospel with other inmates like no one else can.

The missionaries carry what they learned in seminary into the prisons’ living areas to help men “experience God.” In one year alone, they baptized more than 150 prisoners and averaged more than 15,000 evangelistic contacts a month throughout the state’s correctional system.

Cain raised corrections officers’ wages and instituted vocational training for the inmates. The prison’s standard of living “shot through the roof,” said one officer. Cain also started public speaking courses to prepare inmates to better communicate with others. The prison’s radio station, JSLP at 91.7FM, is endearingly called the “incarceration station.” Staffed by inmates, the station evangelizes by broadcasting uplifting music and sermons 24 hours a day.

As Cain shared what God was doing at Angola, his message prompted private donors to build more chapels on the prison grounds and to support the growing ministry programs.

While Angola is still very much a prison, the violent death rate has declined significantly, along with rapes, drug use and assaults on guards. It is largely due to the seminary inmates living and mingling among the rest of the population, observers note. Inmates can now be found holding prayer services in the yards, in their dormitories and on the work sites. Praise and worship services in the chapels are Holy Spirit-filled and rock with heart-felt gospel music from the inmate musicians and choirs.

“No one looks at a watch during a sermon, ’cause all we got is time,” joked one inmate. “We love Jesus and how he’s changed us from the inside. Even if we ain’t never leaving here standing up, we know where we’re going eventually.”

“For those who might think Angola has gone soft, it hasn’t,” one observer noted. “Prison rules are still rigidly enforced. Break them and pay the consequences. Obey them and life, even at Angola, may be worth living.”

Cain seems unconcerned about the “separation of church and state” issue. The results speak for themselves, Cain maintains. He cites the positive impact his initiatives have had on the Angola prison population. Criticism quickly fades away.

“There’s been a moral awakening in this prison like never before,” observed a veteran corrections officer. “The inmates went from negative to positive. Now there is something to achieve and to work toward. Warden Cain may call it moral rehabilitation to non-believers, but the truth is, Jesus is in this place and hearts are changing. Hope is alive here. Angola has become a peaceful and livable place, where inmates who desire to adapt and make something of themselves can do so. Even if they’ll never get out of here alive.”

–30–

Former newspaperman Dennis Shere’s first book, “Cain’s Redemption,” explores Angola prison’s miraculous transformation. Shere is now an assistant public defender in Kane County, Ill.