LITTLE ROCK, Ark. (BP)–Fifty years ago, nine teenaged students showed up for their first day of class at Little Rock Central High School. Under orders from Arkansas Gov. Orval Faubus, the Arkansas National Guard barred their entrance because the nine “new kids,” later dubbed the Little Rock Nine, were black. Central High was a whites-only school.

Two years earlier, the Little Rock School Board had formulated a plan for racial integration that would begin with the 1957-58 school year. The plan complied with the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision Brown v Board of Education of Topeka, which had ruled that racially segregated schools were unconstitutional. The plan’s implementation divided the community along philosophical and racial lines: It was integrationists versus segregationists, and the crisis played out on the steps of Central High before a national television and radio audience.

The national guardsmen were successful in keeping the Little Rock Nine out of Central High that day, Sept. 9. Local black church leaders led organized prayer vigils and federal civil rights lawyers obtained an injunction against Faubus.

On the morning of Sept. 23, 1957, some police officers sneaked the Little Rock Nine into Central High and integration was accomplished. But this act of integration was short-lived. When segregationist groups heard about it later that day, they threatened a riot. The police escorted the Nine out again.

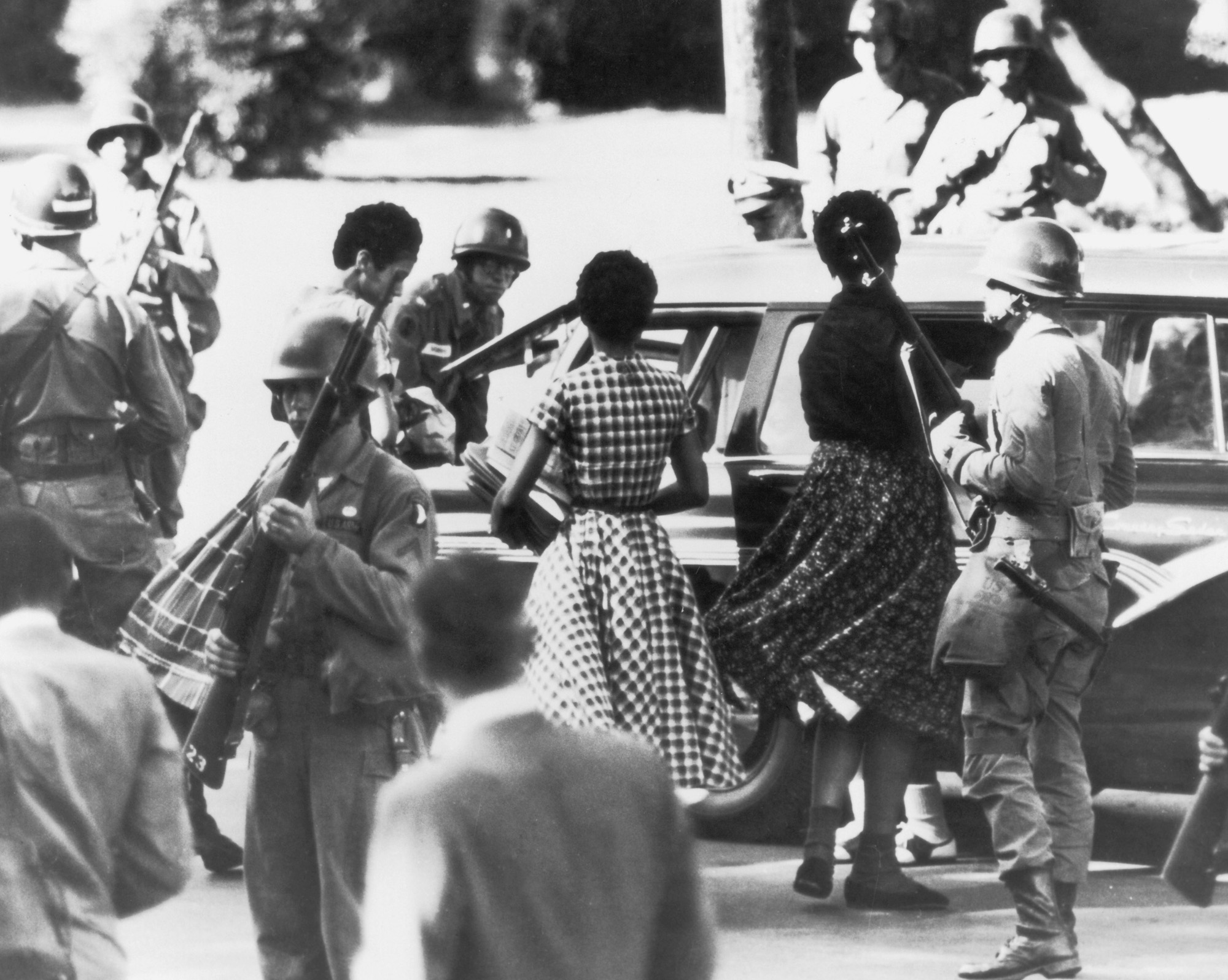

U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower granted a request from the mayor of Little Rock and intervened. Eisenhower ordered federal troops to make sure the black students had access to Central High. The Nine went through the school year accompanied by troop escorts throughout the day.

But the battle raged on. To thwart integration, Faubus caused the cancellation of the 1958-59 school year and closed the high schools. Eventually they were reopened and desegregated beginning with the 1959 fall semester.

Today, racial integration has been achieved among the student population at Central High and the other public schools in Little Rock. Central High is one of the most scholastically high-achieving public high schools in Arkansas and the nation.

Reaction among the churches of Little Rock was divided during the crisis. Even as black churches were organizing prayer and working toward desegregation, many white churches were, essentially, on the side of segregation. The rift between white and black Baptist churches can be measured by the fact that it wasn’t until 1982 that the first predominantly black church associated with the Arkansas Baptist State Convention.

This weekend, the city will observe the 50th anniversary of the integration at Central High. Lectures, roundtable discussions, photo exhibits and other events are being coordinated in part by the Little Rock School District. Among public schools and universities in and around Little Rock, the Central High integration will be celebrated as a great achievement and the Little Rock Nine will be its heroes.

Few Southern Baptist churches in Little Rock will highlight the anniversary. While the Central High crisis established that racial integration of public institutions can be brought about in a community by government action, some Baptists say the voluntary associations that are the hallmark of church fellowship reveal that issues of racial disunity and de facto segregation in churches still prevail.

“I really think the Central High crisis had a tremendous negative effect” on race relations among Baptist churches in the area, said Quinton Moss, the 55-year-old pastor of the predominantly black Unity Bible Baptist Church in Little Rock. Moss is a lifelong Little Rock resident who graduated from another integrated high school in Little Rock in the mid-1960s. For more than 20 years, churches he has pastored or belonged to have associated with the Arkansas Baptist State Convention.

Moss served on the Arkansas convention’s racial unity committee that five years ago studied racial reconciliation issues among ABSC churches. In 2003, ABSC messengers adopted the committee’s report containing recommendations for what churches can do to bring about integration among their congregations.

Moss said it is difficult for both whites and blacks to intentionally reach across generations of conditioning to voluntarily worship together regularly.

“For the most part, some churches embraced the committee’s recommendations, but many did not,” he said. “I have not seen that great a move toward doing it…. We have to intentionally be willing to reach out to the other side to make sure people are welcome.”

The chairman of the unity committee was Larry Page, a white Southern Baptist layman who is the executive director of the Arkansas Faith and Ethics Council. Page agreed with Moss that Baptist churches have to be intentional about racial reconciliation.

“To a large extent, racial reconciliation has been reached in public policy,” Page said. “In churches though, the races are still largely separated into their own congregations and too often they’re not talking, not associating.”

Page said the unity committee noted real progress had been made toward bringing blacks and whites together for worship and service in Southern Baptist churches in Arkansas, particularly when compared with the 1950s. However, he said Little Rock’s churches are much like those in many other communities across the United States that can do more to heal racial divides. “We still have a ways to go,” he said.

Moss believes that racial unity won’t come about until people’s hearts change “on both sides of the aisle” and they get to know each other.

“Early on, great percentages of people in Baptist churches in the South were black -– Negroes –- and blacks and whites worshipped together,” Moss said. “Then after Nat Turner [in August 1831] went in and killed all those people, everyone got afraid. It seems like it is that same type of fear that is out there today.”

Page pointed to Scripture passages such as John 17:20-21 to make the point that Baptists who are white and black should make every effort to come together. There, Jesus prayed for His disciples and said, “I do not pray for these alone, but also for those who will believe in Me through their word; that they all may be one, as You, Father, are in Me, and I in You; that they also may be one in Us, that the world may believe that You sent Me.”

“Our attitudes about race are an inherent contradiction of the Gospel,” Page said. “But we are not to be respecters of persons…. Christians need to be not a mirror of society, but a light for it.”

–30–

Brent Thompson is a freelance writer based in Fort Worth, Texas.