NASHVILLE (BP) — Five months pregnant and already the mother of a toddler, Diane Jordan chose not to attend the 1963 March on Washington. But wanting to help the effort, she and her husband opened their modest home to four black women marchers from Mississippi.

Diane and her husband Monclief “Monty” Jordan, at that time assistant pastor of National Baptist Memorial Church in Washington, were among many white families who provided overnight housing for blacks blocked from hotel accommodations by segregation.

Diane and her husband Monclief “Monty” Jordan, at that time assistant pastor of National Baptist Memorial Church in Washington, were among many white families who provided overnight housing for blacks blocked from hotel accommodations by segregation.

Today, a 78-year-old widow and active member of First Baptist Church in Nashville, Jordan told Baptist Press she wishes she had made every effort to attend the historic event.

“If I had only known how historic it was going to be, we would have made every effort,” Jordan said. “But I had a 3-year-old and I was five months pregnant and, you know, getting out in that crowd didn’t sound like a good idea. But I wish I’d done it now of course.

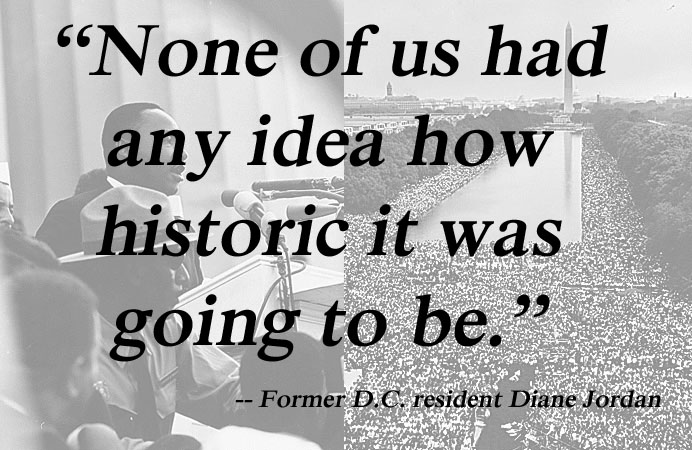

“None of us had any idea how historic it was going to be. You look back and say, ‘Wow, I was part of history.'”

In hosting the Mississippi women, the Jordans answered a community-wide plea from the ministerial association of D.C. to enlist homeowners for housing marchers. Christian and Jewish clergy supported the efforts, Jordan said.

“They got a really good response…. Lots and lots of people volunteered,” Jordan recounted. “We had four ladies from Mississippi and … they were so scared when they got there. Poor things, I would have been too. It didn’t take long for the ice to melt and we just had a good time together.

“But we just had a two-bedroom, one-bath house,” Jordan said. “And I look back, I feel kind of embarrassed. We didn’t have much space for them.”

When the four marchers arrived the Tuesday night before the historic day, Jordan invited them to dine with her family. “And then we went to bed and had breakfast the next morning.” Everyone shared the one bathroom, “and they were so gracious about it,” Jordan said.

“We should have said give us your addresses and all. Looking back, you think, ‘Why didn’t we arrange to stay in touch?’ We didn’t. We haven’t heard from them, but it was a good experience. They were just as gracious as they could be.”

As the women left for the march, the Jordans settled down to watch the event on television.

“We were glued to the set.”

Tens of thousands began to gather on the lawn of the Lincoln Memorial. By the time Martin Luther King Jr. gave his memorialized “I Have a Dream” speech, the crowd was estimated to be as many as 250,000, a mix of ethnicities and economic strata, encompassing Hollywood celebrities, musicians, vocalists, clergy, students, business owners and laborers, spanning from children to the elderly.

“There were certainly a number of whites there and we were quite supportive of it,” Jordan said. “We had no idea what was going to happen. Our take on it was ‘something has to be done, that things are just not fair, things were not right.’ … And of course we were so horrified when we’d see these images of fire hoses and dogs and you just would think this can’t be. How can people be doing these things? [We were] just so horrified….

“We were just hoping that [the march] would help and of course it did,” Jordan said, adding as one example, “It’s so wonderful that we have an African American president.”

News reports preceding the march, including the Aug. 25, 1963, “Meet the Press” broadcast, vocalized a fear among some that such a large crowd would turn to violence. Police officers were stationed across the march site, but both the crowd and law enforcement were friendly, according to historical accounts.

“With that many people descending on the city and not really anywhere for them to stay besides just in peoples’ homes, for them to be so peaceful. I don’t remember that there were any problems,” Jordan said. “You’d think there’d be a skirmish somewhere, you know, people being people, but there was just nothing. It was just amazing.

“Of course his speech just blew us away; it was just so inspired,” Jordan said. “But we just thought this is going to be something that was going to be remembered. It was just most, most impressive.”

King’s 18-minute speech was his first to be televised in its entirety. King’s oratorical expertise came as no surprise to the Jordans, as her brother-in-law, the late DuPree Jordan, became friends with King while the two were classmates at Crozer Theological Seminary.

The Jordans stayed in Washington during the turbulent 1960s. After five years as assistant pastor at National Baptist Memorial Church, a ministry dually aligned with the Southern Baptist Convention and the American Baptist Convention, the Jordans moved to a community on the edge of the inner city. There, Monty Jordan was senior pastor of Covenant Baptist church, also dually aligned with the SBC and ABC.

Monty Jordan was invited to speak at a nearby Baptist church during Easter week of 1968. Days before the service at the African American church, King was assassinated. Jordan’s husband offered to reschedule because of King’s funeral.

“The pastor said, ‘No indeed. We’ve never needed it more. We’re going right on with our service,'” Jordan said. “Monty went to speak…. And it was all black except for one German couple, a white couple, up in the balcony. [Monty said the congregation was] just wonderful….

“And at the end, he felt sure that every single person came through and shook his hand…. They were just weeping and holding his hand and saying this just means everything to us that you were here. I just get choked up talking about it.

“We needed each other because we were all hurting. And [Monty] said, ‘I’ve never felt so close to God or felt more powerfully the presence of the Holy Spirit than I did in that service that day.’” Monty Jordan died nearly two years ago, after the couple settled in Brentwood, a Nashville suburb.

The Christian church has made much progress in race relations -– “certainly way, way beyond what it was when I was a child when there was just no integration,” said Jordan, who grew up in racially charged Birmingham. “But it’s just not nearly what it ought to be. Part of it is I think just worship styles and that sort of thing. But obviously we could do a so much better job than we do.

“I think attitudes are changing tremendously. I think the positive thing is that the … children and young people don’t even notice … what color a friend is. It just matters not at all to them. So to me that’s the hopeful sign, that things will be different as [these youth] begin to get in positions of leadership.”

The story of the church’s involvement in the Civil Rights Movement needs to be told, Jordan said.

The media is quick to report when a church falls short of Christian ideals, Jordan said. “And so when something good comes along, you don’t hear about that. And I think it’s important for people to know that there are, quietly in the background, some good things going on.”

–30–

Diana Chandler is Baptist Press’ staff writer. Get Baptist Press headlines and breaking news on Twitter (@BaptistPress), Facebook (Facebook.com/BaptistPress) and in your email (baptistpress.com/SubscribeBP.asp).