KANSAS CITY, Mo. (BP)–He was a slave. Ripped from his family, severely beaten, forced to live like an animal. Rol Deng knows about persecution. And he wants American Christians to know and to pray about their fellow believers in Sudan who are being killed or sold into slavery because of their faith.

“We are dying for Christ,” Deng said. “Jesus Christ died for us, and that is why we are dying. We need Christian brothers to find a way to unify to help Sudan. Pray for us.”

Deng, who with his family now lives in Kansas City, said his war-torn homeland of Sudan is ruled by Muslims who oppose Christianity.

“There is no work unless you are Muslim,” he said. “The government keeps track. They want to send you to religious training to be Muslim. If you say no, then there is no job.”

Civil war has been raging in Sudan since 1983. More than 2 million people have died during the war, which pits Arabs in the north against Africans in the south. Tensions are rooted in attempts to impose Islamic values on all Sudanese people.

The U.S. Committee for Refugees reports that an estimated 300 Sudanese die each day of war-related causes, including disease and famine.

For Rol Deng, life forever changed one day in 1990. The government sent militia to his village of Arkeyna. Before they left, the whole village was burned, and his father was killed.

Deng, his sister, his mother and three brothers were taken as slaves. A scar running up the side of his leg is a reminder of the beating he endured that day.

In anguish, Deng was forced to ride a camel with other village survivors after the town was razed. That day was the last time he saw his mother and his brothers.

His sister, Ayal, a toddler then, stayed with him. For the next two years, he was forced — at gunpoint — to care for cows in the middle of a field, the climate cold and rainy.

“I had to sleep with the cows. I had no blanket. I ate with the dog. I lived like an animal for two years.”

Eventually, Deng and Ayal escaped their captors by following railroad tracks. Heading north to avoid an increased militia presence in the south, they went in search of a city.

When they came to Babanis, Sudan, they hurried into a church, looking for help. The preacher there told them not to leave. He hid them until he secured tickets to Khartoum and some money for the two.

From 1992-96, Deng and Ayal lived as outcasts outside Khartoum in an area for displaced people. While there, he learned English. Also, it was during this time that Deng met and married Adut.

With only a cardboard shelter to sleep under and the food being designated for Muslims, Deng grew weary of not being able to provide for his family. He knew Christians were forbidden to go into Khartoum, but he was desperate to find work.

While traveling on the road, he was arrested by security forces. The plan was to train him for three months to be a soldier, and then he would be forced to fight.

“I couldn’t do that,” Deng said. “I couldn’t kill my own people.” He escaped and returned to his family. But that was only a temporary solution. He knew he would be found and killed.

The only thing to do was to try to escape to Egypt. Through contact with a relative who worked for the government, Deng, Ayal, his wife, Adut, and their daughter, Adeng, were able to secure money for immigration.

Then, with the help of a security officer who was a secret Christian, they were taken to a boat in the middle of the night. They traveled by boat and then by train to their destination. The officer, who risked his life to save theirs, directed them to the boat and asked them not to look back at him, or ever to mention his name.

Deng found factory work in Abbiasa, Egypt, a place that was friendly to the refugees. But it was difficult to earn enough to support his family, which now included a son, Dut, and another daughter, Amou.

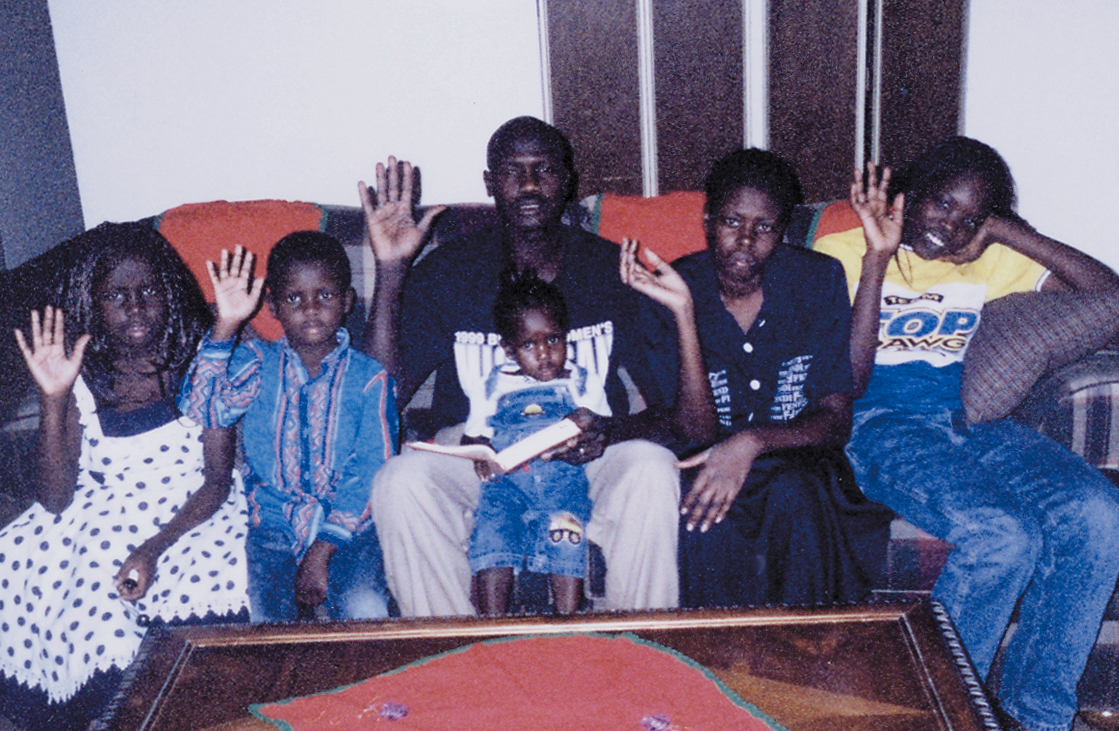

With assistance from the Red Cross, the family came to the United States as refugees on July 21, 2000. The Dengs, along with fellow Sudanese Christians in the Kansas City area, worship in their native language of Dinka at a Nazarene church.

While these refugees from Sudan are grateful to finally live in a country where they can be free to worship Christ without fear, they still carry the scars of their faithful persistence.

Joseph Resendiz, an internist at Samuel U. Rodgers Community Health Center in Kansas City, sees a large number of Sudanese patients. He noted that they frequently have multiple complaints, mostly stemming from years of oppression in their home country.

“Many of them, both men and women, have virtually been slaves,” Resendiz said. “They have told me of widespread beatings, hard labor, rape and torture that characterized their tenure as slaves.

“It is hard to believe that slavery exists in this day and age. In our country, we fight for guns and drugs and money. Over there, they fight for their faith.”

–30-

Martin is a medical social worker in Kansas City and a 1985 graduate of Southwest Baptist University in Bolivar, Mo. For more information about Sudan, contact Samaritan’s Purse at (828) 262-1980; Christian Solidarity International, toll-free 1-888-676-5700; or Freedom House, (202) 296-5101. Their websites are www.csi-int.ch and www.freedomhouse.org.(BP) photo posted in the BP Photo Library at http://www.bpnews.net. Photo title: HEARTS FOR SUDAN.